Reaching meaningful versions is more than setting a number within a package's main file (e.g., package.json, pubspec.yaml, etc.). Versioning aims to build up quality metadata that humans and computers can understand. With this metadata, you can understand the impact a change will have downstream and communicate with users more effectively.

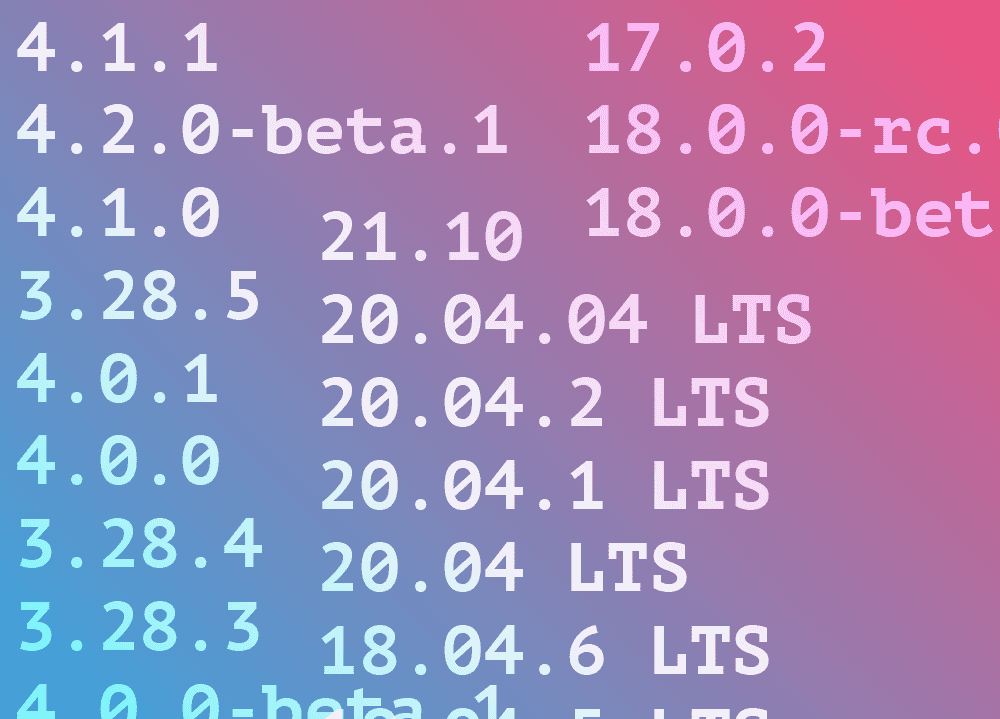

The two most common versioning schemes—SemVer (semantic versioning) and CalVer (calendar versioning)—can help you build the desired aggregated understanding. But going with either of them is not a boolean choice but a spectrum whose adherence specifications you must outline depending on your project's needs and circumstances.

For instance, strict SemVer tends to have the most value in libraries because it is easy to offer rationales for changes and tie them to version numbers. But as codebases become larger and more multifaceted or marketing gets involved, the decision to cut a major version release becomes less about breaking changes and more driven by external factors.

On the other hand, projects with large, shifting codebases tend to prefer using the year for the major version. This works particularly well if there is a Long Term Support (LTS) and maintenance release schedule, as in the case of Ubuntu. It might also lend itself well as a scheme for marketing purposes.

In this article, I'll outline the notions behind SemVer and CalVer and then propose considerations for which versioning scheme to use depending on whether your project is a library, an app, a service that expects breakage, or an additive-only service.

What is SemVer?

SemVer's fundamental rules are simple:

Given a version number MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH, increment the:

1. MAJOR version when you make incompatible API changes,

2. MINOR version when you add functionality in a backward-compatible manner, and

3. PATCH version when you make backward-compatible bug fixes.However, it is hard to track which version we are dealing with in a living codebase with dozens of developers continuously contributing changes. Thankfully, teams can nowadays set up tools like changesets or covector (for monorepos) to automatically aggregate versions. That means that the team must clearly define bump strategies so that all developers have a consistent understanding of the different kinds of changes.

Furthermore, adhering to SemVer's strict definition is not always convenient. For instance, a project may only rely on a MAJOR.MINOR and group all bug fixes and features into a minor release. Or a team may use MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH internally when publishing and releasing, but only publicly release the MAJOR version for consumption. The critical consideration is that the strategy employed is communicated clearly and then consistently used.

What is CalVer?

While SemVer proposes rules that determine the version number, CalVer invites its adopters to define their scheme, considering how time impacts their project. The scheme structure is similar, MAJOR.MINOR.MICRO, but what each segment means is more fluid. In most cases, the MAJOR number is linked to the year of the release. For MINOR and MICRO, CalVer adopters use ad-hoc strategies and combine notions from SemVer.

CalVer has natural synergies with marketing schedules, as they can be tied to the shared time-based milestones.

Versioning considerations by project nature

One way to resolve the question of which versioning model to adopt is to let the nature of your project decide for you.

Libraries

A library lends itself well to versioning using SemVer. Smaller scoped libraries with well-understood changes and impacts can more naturally adopt SemVer in a relatively strict manner. But as the velocity of code (the number of commits in a given period) increases and inter-dependencies build up, decisions around major and minor become more involved, and you might choose to loosen the stringent requirements.

As code velocity increases, it makes sense to group commits into larger releases. But as this progression happens, it becomes more challenging to release a package separate from other changes that have been committed to the monorepo. In light of this, SemVer allows for dependencies within a monorepo to calculate a bump for related packages in response to a specific code change.

Web apps / mobile apps

The value and schema of a version number have different expectations in web or mobile apps because users will rarely be concerned about it. Thus the choice between SemVer and CalVer lies less in the nature of the codebase nature or its users but rather in external influences. A user may not see internal shifts in the code, but they will notice an extensive design refresh, which is often tied to marketing efforts.

The different expectation doesn't necessarily dictate one option over the other, as either would allow communication between the user and support and the user/support to the developer. Instead, the release cadence and marketing schedules will most likely dictate the versioning scheme. The app may have a plan that best matches releases at CalVer’s specific time intervals, which is often seen in Tax prep software offerings. If there is no synergy with other departments, following SemVer is probably simpler for developers.

Services that expect breakages

Services such as REST are designed with the expectation of breaking changes and it is common for REST APIs to use the major version within the URL. The incremental changes may be internally considered a minor and a patch version, but the external version may only be a major version. The SemVer scheme seems to lend itself well to services, but maintaining many service versions increases complexity.

Additive-only Services

An additive-only schema paradigm (where every change can only add to the schema and not cause any breaking changes) has recently come to the forefront. This paradigm devalues major, minor, and patch use, as every release should theoretically be minor. However, in reality there could be breaking changes, but such changes would be elegantly handled through deprecations. As the schema is adjusted, fields can be marked as deprecated. These fields still allow use but will be monitored, and completely removed from the schema when their activity falls below a threshold (while this is technically a breaking change, messaging about a major change does not need to be created to prepare developers to make these changes on a timed schedule).

In light of this rhythm, a case could be made for CalVer. Deprecated fields below the activity threshold could be removed on an annual cadence and the major version bumped to a new year. Every other change only needs to communicate the addition to the schema, expressed by bumping the second number or minor version (there may not be value in using a patch version in this situation).

Conclusion and Recommendations

In general, developers find it easier to work with a SemVer scheme because it's more intuitive given that it's closer to the code. But as projects grow, more considerations have to be made to define a versioning scheme that communicates effectively with users.

It is also not uncommon for projects to change their versioning scheme as they evolve. A project started using strict SemVer doesn’t have stick with that approach; don't be afraid of revising that decision further down the line if it's causing churn or confusion for developers, users, or other teams.

But no matter what you decide, explicit definitions of your versioning scheme helps developers and users navigate changes and expectations over time. Be sure that these norms are written down and accessible for all stakeholders.